Social Security Taxes and the TSP

November 28, 2012

Were you given the “three-legged stool” metaphor by government recruiters prior to beginning a career with the government? I was. During the retirement benefits discussion, I was told that retirement from government would be supported by three legs, which represented a basic government pension, Social Security, and a defined contribution plan (the Thrift Savings Plan). Military personnel receive essentially the same benefits, although in lieu of matching contributions to the TSP, military personnel receive a higher pension at a younger age.

The question we have to ask ourselves is, how sturdy are each of those legs? One leg, at least, is now getting more expensive.

In 2011 and 2012, the “Old Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance” (OASDI) tax rate – that is, the Social Security tax rate – was reduced by 2 percentage points for employees, including military and federal government employees. This reduced what had been a 6.2% tax rate on earned income up to $110,100 in 2012 to a 4.2% percent tax rate for employees. Employers still paid an additional 6.2% tax on top of employees’ reduced 4.2% tax rate for Social Security. Decreased tax rates meant more money in our pockets – an instant raise.

In 2013, the 4.2% tax rate is scheduled to return to 6.2%, unless action is taken to extend the temporary tax reduction.

Since they are tax-deferred – made before taxes are paid – TSP contributions could therefore soften the impact of the higher Social Security tax somewhat, right? Some might think, after all, that the TSP contributions are made before both federal and Social Security taxes are paid. If this were the case, the increased Social Security tax would come out of a smaller post-contribution paycheck.

But this is incorrect.

Social Security taxes – which fall under the “Federal Insurance Contributions Act” or FICA – are paid from gross wages regardless of tax-deferred contributions.

Contributions to traditional TSP accounts, like those made to private-sector 401(k) plans, are “subject to Social Security (FICA) and Medicare” taxes, according to the IRS. The contributions are not subject to federal taxes (and state taxes, depending on the state), but they are made after Social Security taxes. Federal taxes are paid upon withdrawal of TSP funds.

So Social Security taxes are going up, but there is no way to mitigate paying the higher taxes through tax-deferred contributions to the TSP (and to Health Savings Accounts or HSAs, for that matter).

Those making contributions to Roth TSP accounts must also pay federal and state taxes along with Social Security taxes prior to making contributions, but withdrawals after age 59 ½ are free from federal taxes.

So regardless of how participants make contributions to their TSP accounts – traditional or Roth – TSP participants will pay the full 6.2% Social Security tax rate when it is reinstated. The Social Security tax is taxed on income up to a certain limit (see the ssa.gov site here for the exact limit each year), and income above this amount is not subject to Social Security tax.

And then there is the “Hospital Insurance” program, commonly known as Medicare. The rate has been 1.45% since 1986 and was unaffected by the reduction in the OASDI taxes. Unlike OASDI, this tax is paid on all wages without limit.

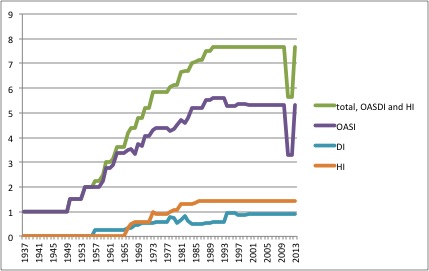

This return to the normal tax rate – an increase of two percentage points – might not seem like much, until you realize that the general trend in these taxes over the past 70 years has been up. Here is a graph of the increase in FICA taxes since the Social Security program was first established in 1936, with an initial 1% tax rate.

OASDI stands for “Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance,” and it is a combination of the “Old-Age and Survivors Insurance” program and the “Disability Insurance” program. OASI began in 1937, and DI began in 1957. In 2013, these will return to their original 5.3% and 0.9% tax rates respectively. “HI” stands for Hospital Insurance – Medicare – which was first established in 1966; employees currently pay a 1.45% tax rate for HI. The total tax rate for employees is scheduled to return to 7.65% in 2013. Employers pay an additional 7.65%, for a total contribution to these programs of 15.3% of an employee’s wages up to certain income limits. (See the Social Security Administration Web site for the complete breakdown of figures.)

And despite the noticeably upward trend in these tax rates over the past 70 years, Social Security and Medicare still have massive unfunded liabilities. The 2012 Medicare Trustees Report, for example, estimated that over the next 75 years, “the additional resources that would be necessary to meet projected expenditures…is $38.6 trillion” (my emphasis added – see pages 289-290 for details). This means that even the restored taxes cannot pay for current promises to pay current and future recipients, so either taxes have to go up even further, current promises of benefits have to be trimmed, or both. To put this unfunded liability into perspective, this figure is more than double than the current U.S. debt of $16 trillion. The estimate is also most likely too low, given increasing lifespan of Americans – a good thing to be sure, but an expensive one in light of current fiscal difficulties.

It is also important to note that unlike individual TSP accounts, individuals do not “own” their Social Security. Social Security payments can be reduced (or even eliminated) at any time, based on congressional legislation. As the Social Security Administration explains:

“like all federal entitlement programs, Congress can change the rules regarding eligibility – and it has done so many times over the years. The rules can be made more generous, or they can be made more restrictive. Benefits which are granted at one time can be withdrawn, as for example with student benefits, which were substantially scaled-back in the 1983 Amendments.”

Since Social Security tax payments are not a “property right,” those who have paid Social Security taxes do not have a right to bequeath it after they pass away or otherwise use it as they see fit in their later years. If a Social Security recipient died a month after retiring, and he or she did not have dependents, all of those years of paying into Social Security simply go to other Social Security recipients.

An individual TSP account, in contrast, is a property right, and neither Congress nor any federal agency can take this right away without going through the courts first. And there would have to be a compelling reason to seize an individual’s TSP account, for example if the owner were convicted of a serious crime.

Thus the Social Security stool leg is feeling increasingly unstable – and increasingly expensive. I’ll discuss the second stool leg (pensions) in another post, but the likely trend is for greater individual contributions to fund pensions, which in turn decreases take-home pay. Individuals only have direct control over the third stool leg, their TSP accounts.

So by all means, keep contributing to your TSP accounts (and for that matter, to HSAs) – it is certainly a better route to building wealth and personal independence than relying on retirement benefits such as Social Security (and Medicare), given their - our - massive unfunded liabilities.

Related topics: annuities hsa